Perceptron or the Grandfather of Neural Networks

What is a perceptron, why is it needed, and how we transferred responsibility for algorithms to the machine.

Where Did It Come From

Before all sorts of abstruse concepts of machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning appeared, people wrote code by clearly formulating the conditions for its execution.

Nowadays, such code would look like a collection of if-else statements or even worse, iterating through values in one if:

if a == 1 and b == 1 and c != 1 and d == 1 and e == 1:

y = 1

else:

y = 0

That is, the developer comes up with some rule or set of rules and describes it. And the computer executes this rule.

Actually, this is okay, but what to do if there are so many conditions that the code becomes unreadable?

And what to do if we have learned to determine something intuitively, but it's hard for us to formulate clear rules?

This problem can be solved by the perceptron.

A Bit of History

In 1957, Frank Rosenblatt created the concept of the perceptron.

However, due to criticism from contemporaries (Minsky and Papert in 1969), who reasonably pointed out the fundamental limitations of a single-layer perceptron, interest in neural networks fell for almost two decades.

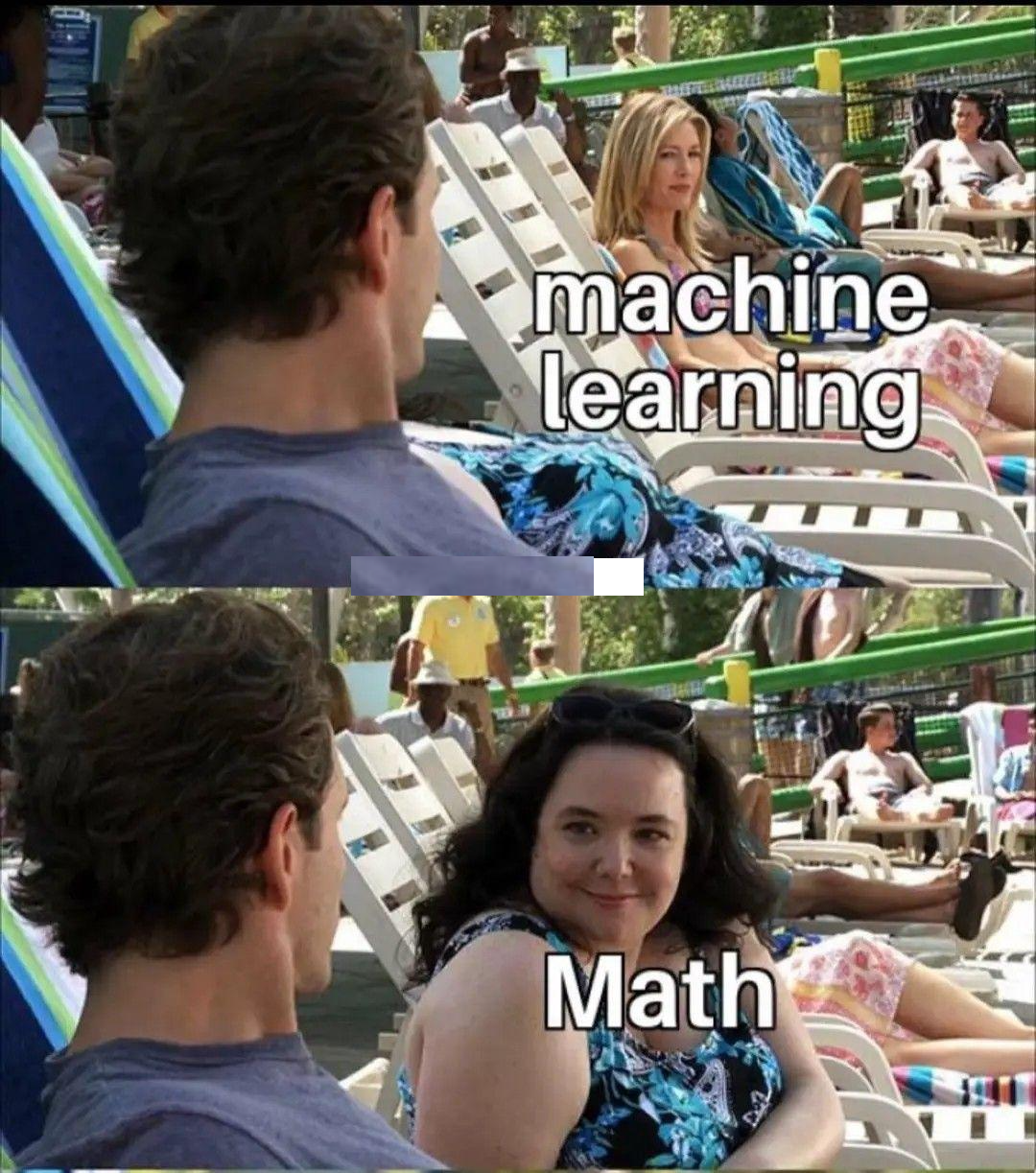

Why is This Perceptron So Interesting?

A paradigm shift in thinking.

The perceptron, as an ideal worker, can tell us:

Don't tell me the rule, give me examples. I'll find the solution myself.

Indeed, it happens that the tasks we face:

- have no rules at all

- have too many rules

- have rules that often change

- have rules that are incomprehensible to us.

For example, can we always clearly understand:

- whether a user is good or bad

- whether a message is spam or normal

- whether an operation is dangerous or not

A Simple Question, How Many Factors

There are many examples, but let's analyze the simplest one that will be close to all of us.

Should I go for a walk today or not?

Imagine how many factors can prevent us from going outside, and how many factors can force us. I'll give a small part as an example:

- Is the weather good today?

- Do I have a meeting scheduled outside?

- Am I sick right now?

- Do I need to walk the dog?

- Have I reached my step goal today?

- Is it raining outside?

- Is there sun outside?

- Did I walk yesterday?

- Have I walked a lot this week?

- Do I need to lose weight?

I'm sure that besides these examples, you could name 10 more, or maybe 100 more questions that could determine the fate of your walk.

It would be difficult to put all these conditions into code to find the perfect algorithm.

And there won't even be a perfect algorithm in that case. After all, it's not just a combination of ifs and elses. Each factor (question) has its own weight.

After all, sometimes even if it's raining, we'll still go outside, for example, if we have a meeting scheduled. And sometimes we won't go to a meeting, for example, if we're sick.

From this we can conclude that there can be many factors for us to make decisions, but not all of them have equal strength. Each factor has its own weight.

The Magic of the Perceptron

The magic of the perceptron is that it can calculate these weights, which gives us a fairly clear answer to the question of whether we'll go for a walk today or not.

To make it easier for us to understand how the perceptron does this, let's assume that there are only two factors that determine our answer to the question "Are we going for a walk today or not?"

- Is there sun outside?

- Is it raining outside?

Each of these features has its own weight.

Let's assume that we go outside only if there's sun and no rain.

Sun Rain → Walking?

1 0 1 ✅

1 1 0 ❌

0 1 0 ❌

0 0 0 ❌

Obviously, sun is an argument "FOR", rain is an argument "AGAINST". These are our arguments, they have their weight.

Besides arguments, there is almost always also the general mood (for zoomers it's vibe).

For example, our laziness.

The general mood is called bias. This is how strict or lazy we are in general, even if there are no arguments.

What is the Point of the Perceptron's Work?

It does only one thing.

The perceptron calculates the result of multiplication and addition and compares the result with zero. If the prediction does not match the correct answer, we correct the weights and bias and try again.

Let's go back to our weather. Let's try to make an expression according to perceptron rules, but for now without numbers.

How can we determine whether we'll go outside or not:

result = ☀️ * sun weight + 🌧 * rain weight + my laziness(bias)

We compare our result with zero, as the perceptron does.

if result > 0

final = 1

if result <= 0

final = 0

Something similar happens in our head every time we make decisions. Frank Rosenblatt, as a psychologist, was able to represent this in the form of multiplications and additions 🤯

The result we got, we compare with the final result that was given to us initially.

If the result matches, then we keep the argument weights and bias. The perceptron worked as it should. When the same data comes to us again, we will already know how much each argument weighs, how lazy we are, and we can easily give the correct answer.

If the result does not match, then we correct the argument weights and bias. And try to calculate the result again. We do this until we find those very weights and biases that will give us peace and tranquility.

Now let's try to add at least some numbers. Let's write a small snippet in Python:

Input Data

# Sun, Rain, Correct Answer (Walking?)

data = [

(1, 0, 1), # sun, no rain → walking

(1, 1, 0), # sun + rain → not walking

(0, 1, 0), # no sun, rain → not walking

(0, 0, 0), # no sun, no rain → not walking

]

- The first two numbers are arguments.

- The last one is the correct answer.

Weights and Bias

To not poke around blindly, let's start with zeros:

w_sun = 0.0 # sun weight

w_rain = 0.0 # rain weight

The perceptron doesn't know anything, it's neutral to everything for now.

However, we know that laziness hinders us more, so let's give it an arbitrary negative value (no one prevents us from setting 0, the perceptron is smart, it will find all the necessary values itself).

lazy = -0.5 # my laziness (bias)

Perceptron Function

This is the heart of the entire model.

def perceptron(sun, rain):

result = sun * w_sun + rain * w_rain + lazy

return 1 if result > 0 else 0

This is exactly the same formula we already saw:

result = ☀️ * sun weight + 🌧 * rain weight + my laziness(bias)

if result > 0

final = 1

if result <= 0

final = 0

Training: trying, making mistakes, correcting weights and bias

"If the result doesn't match — we correct the weights and laziness". This needs to be recorded.

learning_rate = 0.1

This is how strongly we are ready to change the weights and bias.

For now, let's just add this variable, we'll need it later.

Let's try to compare the answers from the data and the perceptron's predictions.

for sun, rain, correct_answer in data:

prediction = perceptron(sun, rain)

error = correct_answer - prediction

Here we understand if we made a mistake or not. If we did, then we can understand in which direction:

- error = 0 → we guessed

- error = 1 → we should have gone, but we didn't

- error = -1 → we went when we shouldn't have

Let me explain this part a bit more, because when I showed this part to my wife, questions arose right here.

error = correct_answer - prediction

I remind you that correct_answer (correct answer) is the last value inside the lists (tuples):

data = [

(1, 0, 1), # sun, no rain → walking

(1, 1, 0), # sun + rain → not walking

(0, 1, 0), # no sun, rain → not walking

(0, 0, 0), # no sun, no rain → not walking

]

That is:

- correct_answer (correct answer) can be that we go or don't go. 1 or 0.

- prediction (perceptron prediction) can be that we go or don't go, that is also 1 or 0.

When we subtract the perceptron's prediction from the correct answer, we can get the following situations:

error = 0 - 0 # 0 - no errors, perceptron's prediction is correct.

error = 1 - 1 # 0 - also no errors, perceptron's prediction is also correct.

Both options imply that the perceptron's predictions are correct. The answers match, we have no need to correct anything.

A different story happens if error becomes equal to 1:

error = 1 - 0 # 1 - we should have gotten 1 (that we go outside),

# but got 0 from perceptron (that we don't go outside)

This means that the perceptron's predictions turned out to be too pessimistic.

That is, we underestimated the weights of the arguments that participated in the decision. For example, the importance of whether there is sun is actually much more significant, suddenly we live in Norway, and sun for us is a particularly strong argument to go outside. We need to increase the weight.

And what to do if error becomes equal to -1?

error = 0 - 1 # -1 we should have gotten 0 (that we don't go outside),

# but got 1 from perceptron (that we go outside)

This means that the perceptron's predictions turned out to be too optimistic.

That is, we overestimated the weights of the arguments that participated in the decision. For example, sun doesn't have such great importance for us, we live in California, sun is year-round, and it's not really important to me whether it's there or not. We need to decrease the weight.

And now there will be real math magic:

Weight Correction (the most important place)

We understand that depending on the error value, we should:

- Either change nothing (when error = 0)

- Or increase weights (when error = 1)

- Or decrease weights (when error = -1)

At the same time, we must remember that we change the weights only of those arguments that participated in the perceptron's decision-making.

We can use beloved if-elses. Then it would look something like this:

# check that sun == 1, that there is sun and at the same time there is an error

if error == 1 and sun == 1:

w_sun = w_sun + learning_rate

elif error == -1 and sun == 1:

w_sun = w_sun - learning_rate

# check that rain == 1, that is, that it was raining, and at the same time still an error

if error == 1 and rain == 1:

w_rain = w_rain + learning_rate

elif error == -1 and rain == 1:

w_rain = w_rain - learning_rate

# in other cases we don't touch the sun or rain weights at all.

But this doesn't look very elegant to call it an "algorithm" or "grandfather of neural networks", so mathematicians came and gave a beautiful solution (which in essence does absolutely the same thing):

w_sun = w_sun + learning_rate * error * sun

w_rain = w_rain + learning_rate * error * rain

This is not magic: if sun = 0, the sun weight doesn't change, because this feature didn't participate in the decision-making.

The same goes for rain.

And What About Laziness?

We'll move laziness always if there's an error.

lazy = lazy + learning_rate * error

Intuitively:

- if sun helped make a mistake → increase its weight

- if rain interfered → decrease

- laziness moves always

Why does bias always move?

Actually, this is quite logical.

Imagine if you get as input that there's no rain and no sun. That is 0 and 0. And we get an error at the same time.

We can't change the sun and rain weights, as we already know. Because in this case they didn't participate in the perceptron's decision-making.

So the only thing that can change the outcome is bias. That is, the general mood. For example, if there's no rain, no sun, and we still go for a walk. Then the general mood is most likely not laziness, but our proactivity (or great love for walks).

From this we can conclude that bias can be a positive number too.

At the same time, it's important to remember that

bias will in any case change in case of perceptron error!

Let's Run Training Several Times

One pass is not enough. Let's repeat several epochs:

for epoch in range(10):

for sun, rain, correct_answer in data:

prediction = perceptron(sun, rain)

error = correct_answer - prediction

w_sun = w_sun + learning_rate * error * sun

w_rain = w_rain + learning_rate * error * rain

lazy = lazy + learning_rate * error

Let's see what we learned

print("Sun weight:", w_sun)

print("Rain weight:", w_rain)

print("Laziness:", lazy)

And now let's check ourselves:

for sun, rain, _ in data:

print(sun, rain, "→", perceptron(sun, rain))

Console output:

Sun weight: 0.3

Rain weight: -0.1

Laziness: -0.2

1 0 → 1

1 1 → 0

0 1 → 0

0 0 → 0

The perceptron learned our rule. We gave it only data, it itself determined the argument weights and the strength of our laziness.

Here's the full snippet:

# Sun, Rain, Correct Answer (Walking?)

data = [

(1, 0, 1), # sun, no rain → walking

(1, 1, 0), # sun + rain → not walking

(0, 1, 0), # no sun, rain → not walking

(0, 0, 0), # no sun, no rain → not walking

]

# The perceptron doesn't know anything, it's neutral to everything for now.

w_sun = 0.0 # sun weight

w_rain = 0.0 # rain weight

lazy = -0.5 # my laziness (bias)

def perceptron(sun, rain):

result = sun * w_sun + rain * w_rain + lazy

return 1 if result > 0 else 0

# How strongly we correct weights

learning_rate = 0.1

# Training, weight correction

# Let's run several times

for epoch in range(10):

for sun, rain, correct_answer in data:

prediction = perceptron(sun, rain)

error = correct_answer - prediction

w_sun = w_sun + learning_rate * error * sun

w_rain = w_rain + learning_rate * error * rain

lazy = lazy + learning_rate * error

# Let's look at the final results at the end:

print("Sun weight:", w_sun)

print("Rain weight:", w_rain)

print("Laziness:", lazy)

# Compare the result with what was given initially:

for sun, rain, _ in data:

print(sun, rain, "→", perceptron(sun, rain))

And How Can This Be Used in Real Life?

Further, this can be used as an ordinary function that will answer the question. Will we go for a walk today or not.

It will look something like this.

def should_go_outside(sun: int, rain: int) -> bool:

prediction = sun * 0.3 + rain * -0.1 - 0.2 # sun weight, rain weight, minus bias(laziness)

return True if prediction > 0 else False

And if the data changes again, then we can run everything through the perceptron function again, getting new weights.

And What?

Why did you read this? Well, it existed and existed, why grumble about some perceptron. They criticized it anyway later.

Perceptron Limitations:

Yes, it was criticized, here are the main limitations of the perceptron:

- It can't handle XOR:

x1 x2 → y

0 0 → 0

0 1 → 1

1 0 → 1

1 1 → 0

x2 ↑

1 | ● ○

|

0 | ○ ●

+----------------→ x1

0 1

● = 1

○ = 0

There is no single straight line that will separate them.

One perceptron is useless in this case. This problem later led to the emergence of multilayer networks.

- The perceptron doesn't know probabilities.

It can only give a hard binary decision. 1 or 0.

This is a problem if:

- risk is needed

- calibration is needed

- thresholds are needed

Therefore, in reality, logistic regression is more often used.

- The perceptron can't build complex dependencies:

If there's sun OR (there's rain AND a meeting is scheduled)

The perceptron can't do parentheses.

It adds everything linearly.

- Works poorly with real data:

Real world:

- noisy

- contradictory

- incomplete

Perceptron:

- expects clear boundaries

- poorly tolerates labeling errors

- breaks with class imbalance

And Why Did I Read This,

Your perceptron doesn't work! Look what neural networks do there, and I'm wasting my time on your old stuff.

Not at all!

It's important and necessary to know about the perceptron. Because it:

- Explains the idea of learning. ML didn't appear right away, we must honor the memory of our grandfathers!

- Teaches us to think in terms of features and weights.

- Teaches us to think not "how to program the rule", but how to let the model find the rule.

Next time, when you try to study again how neural networks work. And for example, decide to watch the video from 3Blue1Brown

You will definitely come across the multilayer perceptron.

I hope that one mystery in your life has become less.

With love to the perceptron ❤️

Sergey Usynin